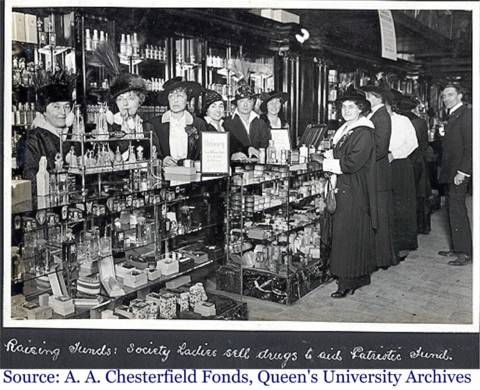

The women in this picture are selling pharmaceutical drugs to help support the Canadian Patriotic Fund. The Canadian Patriotic Fund was a private fundraising organization incorporated in 1914 by federal statute and headed by Montreal businessman and Conservative Member of Parliament Herbert Brown Ames. The fund was established to give financial and social assistance to soldiers' families.

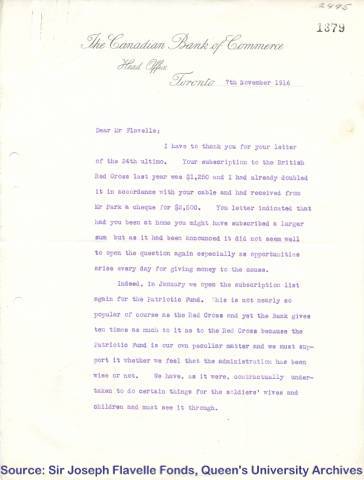

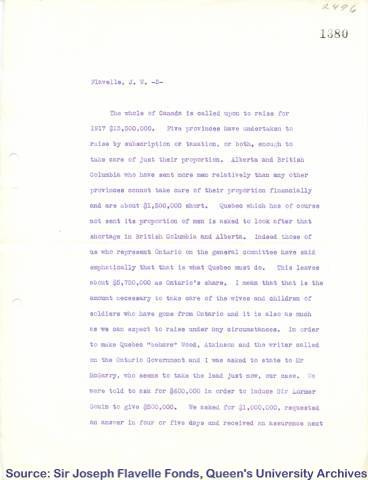

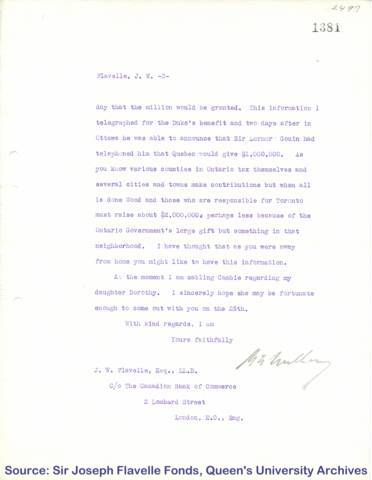

This letter is from a representative at, "The Canadian Bank of Commerce" and is addressed to Sir Joseph Flavelle (chairman of the Imperial Munitions Board). This letter describes the contributions that each province has made to the Canadian Patriotic Fund. In 1917, all of Canada was called upon to raise $13,500,000. Some provinces raised their share through subscription and taxation. Quebec was asked to give more than their share because they did not contribute as many troops to the war effort.

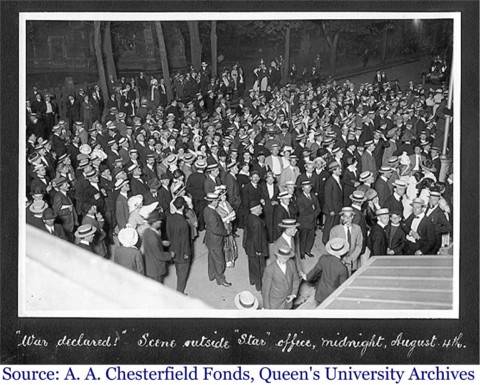

This is a picture of the scene outside the "Star" office, midnight August 4th, 1914. Britain had just officially declared war against Germany. Instantaneously, Canadians gathered in the streets, singing and cheering. Everyone wanted to be a hero and everyone wanted to go to war. Some suggest that those parading and singing in the streets were people unlikely to be affected negatively by the war. Others sat quietly in their homes, afraid and uncertain of the future that war would bring. Many English speaking Canadians believed that the moment Britain declared war, Canada was also at war. There were still some very strong ties to Britain in Canada. People cheered because war meant steady employment for all and it put an end to the depression that was imminent in 1914.

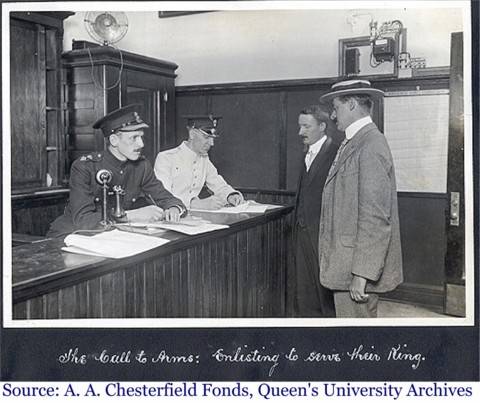

This is a picture of a typical recruiting office in Canada during WWI. Some enlisted because of the steady wage that could be earned in the army (especially farmers), others purely to serve the British empire, and some enlisted just to get a free ride back to Great Britain. Not all volunteers were accepted. Some were refused because they failed the medical exam, or were too young or too small. Others were refused entry because of their ethnic origin. For example, black recruits from Canada rarely saw the battlefield, instead being relegated to construction and cleanup crews. Japanese Canadians were not permitted to form their own battalion in Canada, even though Japan was an ally of Britain during WWI. Recruiting was often directed towards wives and mothers, in an attempt to drive cowardly men into the ranks. Married volunteers were required to obtain the written permission of their spouses before they were eligible for enlistment. The recruiting drive was everywhere, through propaganda posters, celebratory parades, and patriotic speeches. If a man was of able body and age it was looked at as an oddity if he did not enlist.

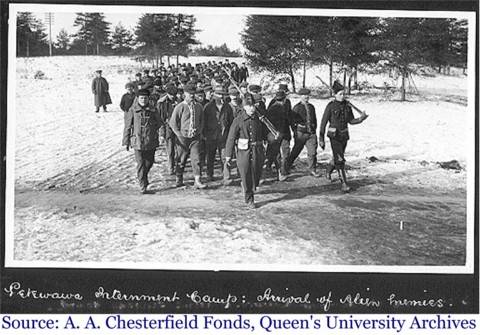

The first photo is a picture of "alien enemies" arriving at the Petawawa Internment Camp during WWI. During the war more than 8,500 immigrants from "enemy" countries (e.g., Ukrainians, Poles, Hungarians, Germans, Croats, Serbs, Slovaks, Turks, and Bulgarians) were placed in internment camps across Canada. Many immigrants were interned for attempting to leave Canada, posing a security threat to the war effort. Others were interned for acting suspiciously, showing resistance to authority, being deemed unreliable or undesirable, or for being found in a state of hiding.

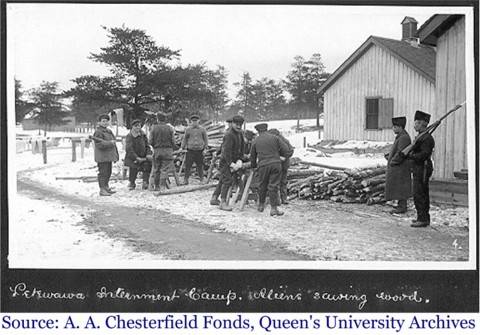

The second photo is a picture of immigrants being forced to do work at the Petawawa Internment Camp during WWI. Many labor bosses in Canada laid off immigrant workers and hired Canadian born workers in an attempt to be patriotic. For this reason, unemployment was very high among the immigrant population of Canada during WWI. Internees were paid only 25 cents for a full day of work (e.g., building roads, building and repairing buildings, and clearing the rugged land of the northern Canadian frontier).

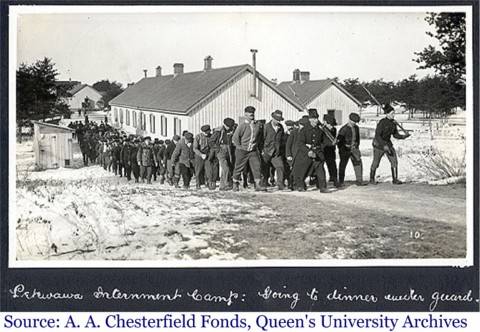

The third photo is a picture of internees being marched off to dinner at the Petawawa Internment Camp during WWI. German internees received the best meals and living conditions. Ukrainians were among those treated the poorest at internment camps in Canada. At one point "enemy aliens" in Canada were required to register at their local registrar's office. They were also required to report monthly and carry special identification cards and travel documents.

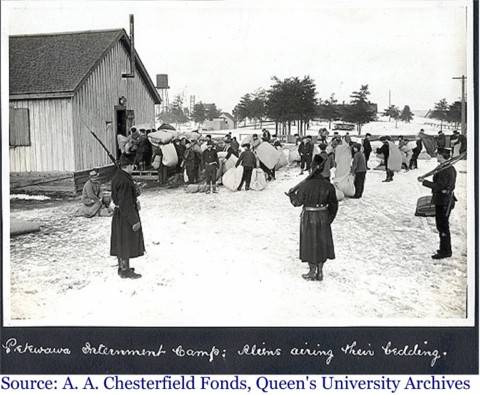

The fourth photo is a picture of internees carrying their beds into the crowded barracks where they slept at the Petawawa Internment Camp during WWI. As the war dragged on into its third year, Canada's labor force became desperate for workers. In response to this, many of the internees or "enemy aliens" were released to work in factories and on farms. Many times they were forced to work in places that were far away from their families.

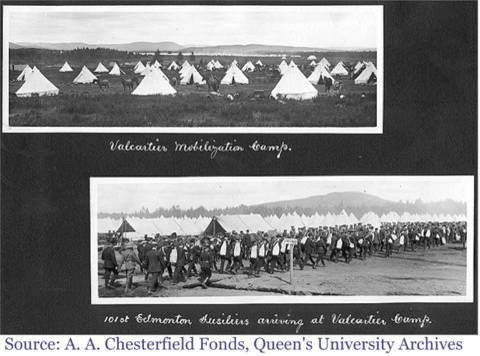

The first picture is of the lodging tents at Valcartier military training camp, located 25 kilometers from Quebec City. Camp Valcartier was hurriedly built in only four weeks to provide a place for the training and mobilization of Canadian troops during World War I. At the start of WWI Valcartier facilitated the training of 32,000 recruits. A great deal of time was spent getting the large number of troops organized into groups.

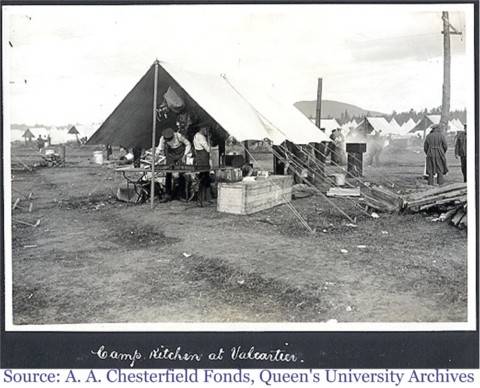

The second picture is a photograph of one of the temporary food kitchens at Valcartier. This is where all of the meals were prepared daily for the hungry troops.

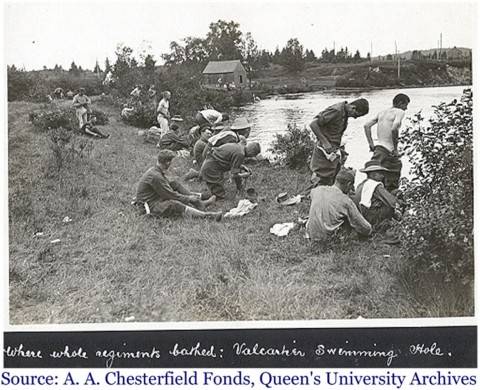

The third photograph is a picture of the bathing facilities at Valcartier. Having a bathtub or shower to clean yourself in was a luxury that Valcartier did not provide. There were different training exercises for each type of soldier that attended Valcartier. For example, bombers, Lewis gunners, rifle grenadiers, riflemen, scouts, and runners all had different daily training exercises. The training focused on preparing the soldiers for the fighting that they would join in just a few short months. Physical fitness was an important part of the training. Sports were used as a means of physical conditioning and to promote cooperation and teamwork within the group.

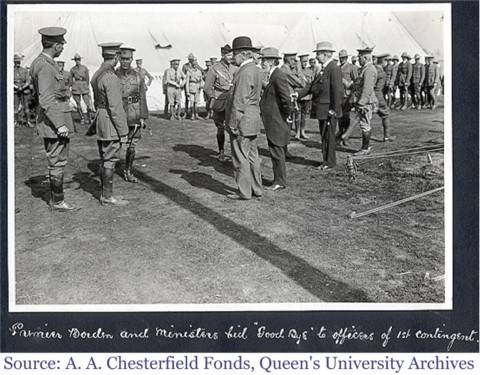

The first picture shows Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden and some of his Cabinet Ministers at Valcartier training camp in Quebec. They are there to show their support for the Canadian Army's 1st Contingent that is being sent to Europe for combat duty. Valcartier is the main training facility for troops being sent to battle during World War I.

The second picture shows Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden and some of his Cabinet Ministers at Valcartier, saying goodbye to officers of Canada's 1st Contingent. Canadian politicians often visited new recruits as a show of support, to encourage them to fight for the good of the country.

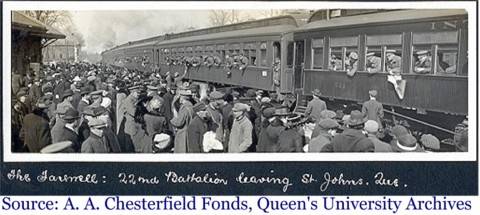

This is a picture of the 22nd Battalion leaving Quebec on a train headed for a troop transport ship that would take them to Britain during WWI. The railways of Canada were used substantially in WWI to mobilize troops. Railways carried troops to training camps, to transport ships, and to their home territories after the war ended in 1918. Canadian railways were also used to facilitate the wartime economy during WWI. Products and workers were transported all over Canada by way of the railroad.

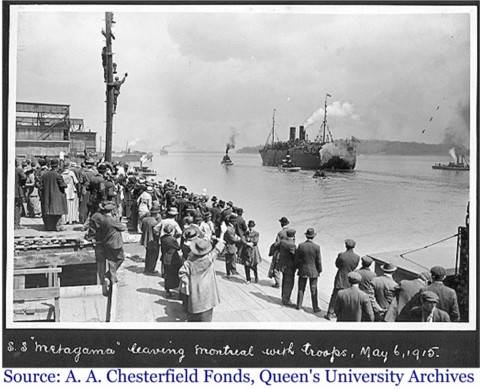

This is a photograph of the S.S. "Metagama" leaving Montreal with troops, May 6, 1915. There are a number of people that have gathered on the shore to see the ship off. These people are likely the friends and relatives of the troops onboard.