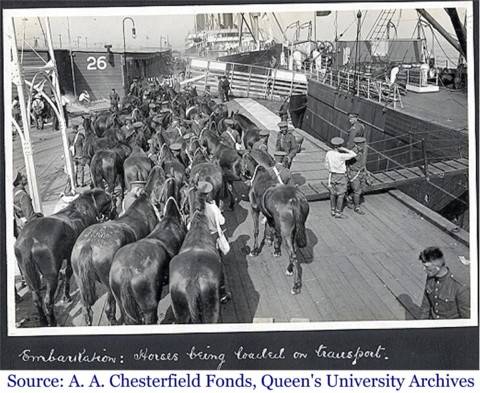

This is a picture of horses being loaded onto a transport ship to be sent overseas to join the war effort. Horses were still being used in great numbers during World War I. High ranked army officers commonly rode horses during World War I. Horses and mules were also used to carry heavy equipment to and from the front during the war. Unfortunately, many of these horses and mules died before they got to the front because of the harsh journey overseas. Horses and mules also died in WWI because of their inability to free themselves from the thick mud. Many others were wounded and killed during battle. There was a tremendous shortage of horses in Canada during the latter stages of WWI.

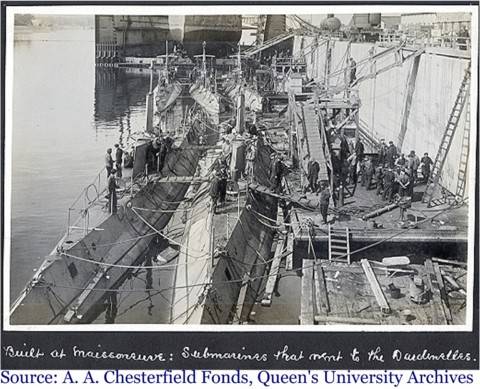

This is a picture of some of the early experimental submarines that were developed during World War I. The submarine was part of the modern style of warfare that was introduced in World War I.

The German navy had approximately 100 submarines in service during WWI. Initially the Germans used submarines to threaten the Allies' economic blockade. In 1917 the German Kaiser declared unrestricted U-boat warfare against the allies, including neutral ships in British waters. In response, the Allies established armed convoys to protect merchant ships and increased production of mines and depth charges. The sinking of neutral ships, like the Lusitania in 1915, polarized public opinion (against the Germans) about the war, and was a major factor in the decision of the United States to join the Allied caused.

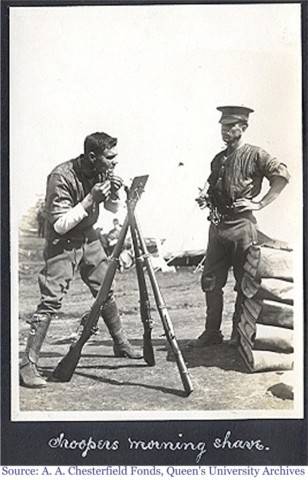

This is a picture of a soldier shaving at Valcartier (a military training camp in Quebec). This particular soldier has cleverly propped a shaving mirror on the top of three rifles to make shaving a little more pleasant. Canadian recruits and conscripts went to camp Valcartier to train for service in the war. The early days of training stressed the traditional methods of warfare used in the Boer War of 1899 (e.g., ceremonial parading, kilts used for uniforms , and bayonets being the most important fighting skill for a soldier to have). The fighting style of WWI was different than any ever experienced before (e.g., trench warfare, tank warfare, air combat, and submarine warfare). Both sides were forced to learn these new techniques on the fly. It was very important for a soldier to be resourceful, flexible and resilient during the early years of modern warfare.

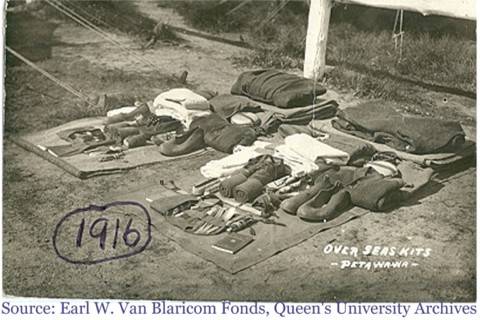

This picture shows an example of a typical equipment kit that was carried by each Canadian soldier while overseas during World War I. Canadian uniforms and equipment were usually of British pattern. Equipment changed throughout the war with the development of better gear, the changing climate, and the evolution of modern warfare. At the outset of war, Canadians either used the Oliver Pattern, Canadian WE08 equipment, or the Mills Burrows WE13 equipment. In March 1916, Canadian troops were issued a two pound Mark 1 steel helmet to protect themselves in the trenches. Troops also carried items like a shovel, rifle, ammunition, knife, water canteen, and a mess tin.

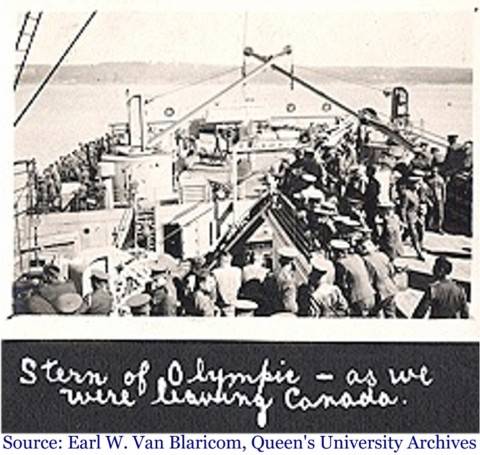

The first photo is a picture of the H.M.S. "Olympic", a boat that was used to transport Canadian troops and equipment overseas during World War I. At the outset of war in 1914, Canada's navy was in shambles, with no more than one broken down cruiser on each coast, 350 officers and men, and about 250 trained members of the Royal Naval Canadian Volunteer Reserve. Prime Minister Borden pleaded with Great Britain to help Canada build a navy but Britain refused and requested only troops and equipment for the army. During the early years of the war, Canadian troops continued their training while onboard these transport ships. Regular fitness exercises and shooting drills were done on the crowded decks of the ship. Some troops were tragically killed by accidents that occurred during this training. Others died on these ships because of poor living conditions that were common on these long journeys.

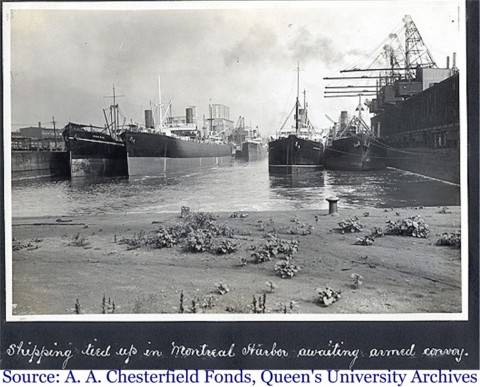

The second photo is another picture of the typical ships that were used to transport troops (fresh and wounded), horses, equipment (artillery, ammunition, weapons, etc.), food, volunteers, and any other items needed during WWI. The transport ships in this picture are waiting at Montreal Harbor for an armed convoy to arrive before they embark on their journey overseas.

The third photo is a close-up picture taken on the deck of the H.M.S. Olympic as it was leaving Canada during WWI. The crowded deck is typical of all troop ships that made there way over to Europe during WWI. The first large load of Canadian troops were carried overseas by thirty-two passenger liners, of which only three were Canadian owned. These ships were escorted by four Royal Navy light cruisers. Armed escorts were used to protect convoys from predacious German U-boats. Forty-five Canadian steamships were sunk by German U-boats during WWI. The Royal Canadian Navy did play a successful and important role in the protection of these convoys throughout WWI. Less than five percent of all ships lost to U-boats during WWI (over 5,000) were lost while being accompanied by an armed escorted.

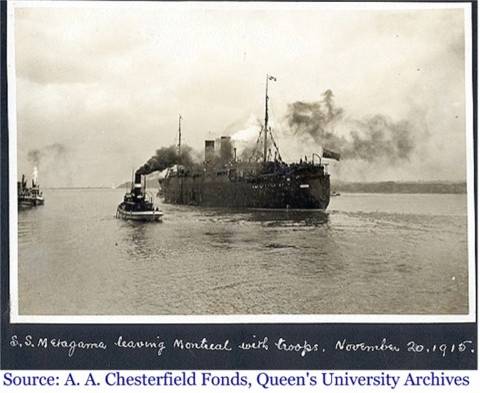

The fourth photo is a picture of the S.S. Metagama leaving Montreal with troops, November 20, 1915. By the end of 1918, the Royal Canadian Navy enlisted more than 9,500, had more than 100 ships (e.g., cruisers, destroyers, submarines, trawlers, minesweepers, and converted civilian vessels), and had a small undeveloped Naval Air Service. Airplanes worked closely with armed escort ships to spot lurking U-boats in the path of the convoy. A national flag merchant fleet, known as the "Canadian Government Merchant Marine" was also developed during WWI. The shipbuilding industry was booming in Canada by the end of WWI.

This is a picture of a British Mark IV tank that had been captured and used by the Germans during World War I. The tank was integral part of the modern style of warfare that evolved during World War I. The tank did not play a major role in the early fighting of World War I, but its effectiveness increased as the war went on.

Tank warfare was first introduced by France and Britain in 1916. These early heavy tanks proved to be ineffective and were soon replaced by lighter versions that soon revolutionized the war. By 1917 the British and French were using 1500 tanks each. Tanks became a regular feature in all offensives and were credited with Allied successes after 1916.

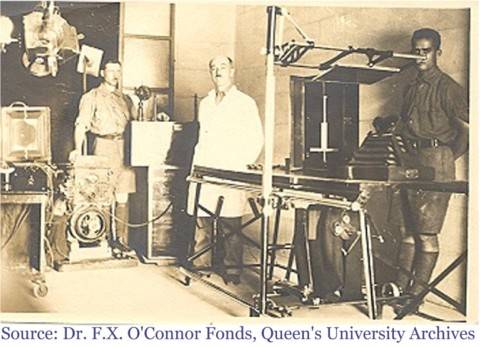

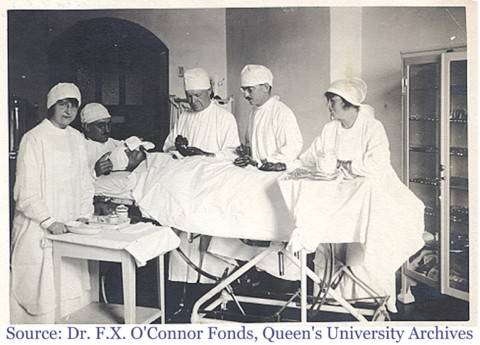

The first photograph is a picture of a medical examination and radiology room during World War I.

The second photograph is a picture of a surgical team performing an operation during World War I. Obvious concerns for surgeons during World War I were gangrene (infection), sterilization, and sanitization. Many times, amputation was necessary because of the inset of infection and the lack of sterilization and sanitization available to surgical teams.

The first picture is of a German plane that was used during World War I. The plane was part of the modern style of warfare that evolved during World War I. Initially, the airplane was used primarily for reconnaissance purposes, to spy on the enemy. The airplane did develop into an offensive weapon by the end of World War I.

The second picture is a painting of a British airplane that is engaged in air combat. This airplane has a machine gun mounted on its top wing.

In 1914 the Allies had 220 airplanes, the Central Powers 258. The Germans also used Zeppelins and by 1918 had over 100 of these airships capable of bombing missions. The German Folker aircraft was an early example of a successful fighter plane. At first pilots used rifles and pistols in air battles, although machine guns were soon introduced. By 1916 the Allied production of aircrafts equalled the Germans and air battles between "aces" like German Richthofen "The Red Baron" (80 victories) and Bishop the Canadian (72 victories) were becoming legendary.

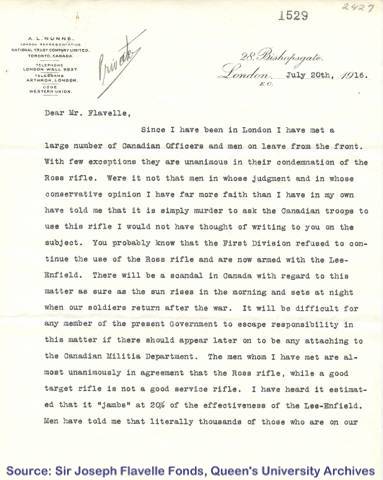

This is a letter from William E. Rundle of the National Trust Company from London on July 20, 1916, addressed to Sir Joseph Flavelle (appointed chairman of the Imperial Munitions Board in late 1915). The letter is concerning the ineffectiveness of the government sponsored Ross Rifle. Canadian officers and troops are growing impatient with the weapon and many refuse to continue using it. The Ross Rifle is said to be a good target rifle but is a very poor service rifle. The Ross Rifle showed a dangerous tendency to jam when it was used in heavy mud and when used with British ammunition. During heavy fighting soldiers often had to kick the bolt open to release the jam. If the rifle was assembled incorrectly the bolt could fly off and severely injure the soldier's face. This letter is an attempt to make the government aware of the potential embarrassment that this situation may cause if Canadian soldiers continue to die because of the ineffectiveness of a government sponsored weapon. Finally in 1916 the Ross rifle was officially replaced by the British Lee Enfield MK III. Ross rifles were only used by snipers for the remainder of the war.

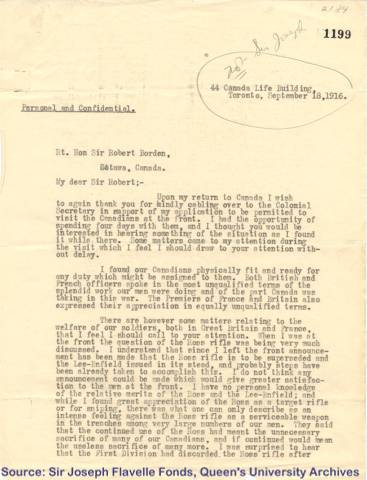

This letter is addressed to Sir Robert Borden (Prime Minister of Canada), written by an unidentified correspondent (probably Sir Joseph Flavelle) on September 18, 1916. This letter is concerning the author's recent visit to Canadian troops at the front in Europe. The author mentions the continued complaints about the Ross Rifle and supports the government's decision to use the British sponsored Lee Enfield rifle. Canadian troops were already anxiously confiscating Lee Enfield rifles from British soldiers that had been killed during battle. Another concern voiced was about the equipment that Canadian troops were being issued (the Oliver equipment). It was very uncomfortable to carry and it was hard to get ammunition quickly in times of emergency. There were also some complaints about defective machine guns and untrained recruits being sent to the front as replacements. There were also complaints about new recruits being in poor physical shape. There is uncertainty at the front about who is in control of the armies. In closing, the author urges Borden to visit the front himself to gain a feel for the dire situation.